Philadelphia Inquirer - October 22, 1980

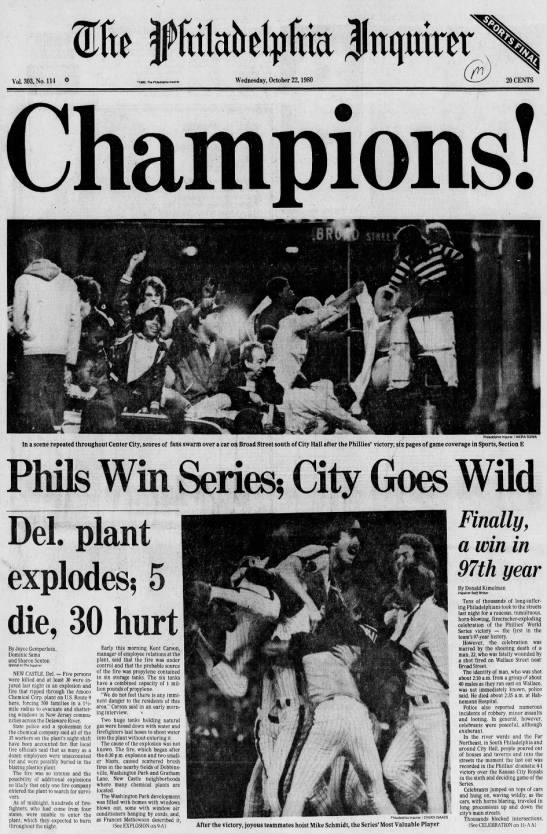

Champions!

Phils Win Series; City Goes Wild

Finally, a win in 97th year

No Author Listed

Believe it. The Phillies have own the World Series.

The scrappy, come-from-behind heroes of October captured the fourth and deciding game last night before a record 65,838 fans at Veterans Stadium, defeating the Kansas City Royals 4-1.

The game ended in typical Phillies gut-wrenching fashion- Tug McGraw throwing the third strike past Willie Wilson with the bases loaded, and the city erupted in celebration of the first world championship in the 97-year history of the Phils, who had lost two previous World Series, in 1915 and 1950.

The Phils took the lead in the third inning, when Bob Boone walked, Lonnie Smith grounded to Royals second baseman Frank White, Pete Rose laid down a perfect bunt and Mike Schmidt singled, scoring Boone and Rose. They scored again in the fifth, when Smith raced home on a grounder by Bake McBride, and again in the sixth on a single by Boone that drove in Larry Bowa.

In the ninth, Rose saved the game by catching a Frank White pop-up that bounced out of Boone's glove, while the bases were loaded. Wilson was the next- and last- batter.

The Phillies won the first two games in the Series, at the Vet, but lost the next two, at Royals Stadium. They captured the third game in Kansas City on Sunday, before ending it all last night.

A happy Green makes the rounds while savoring his moment of glory

By Danny Robbins, Inquirer Staff Writer

The charred Phillies pennant, the one that somehow survived a restaurant fire in Clearwater, Fla., was on the wall. The bottle of bubbly was on the desk. And Dallas Green, first-year manager of the Phillies, was on the phone with President Carter.

When the Phillies had won their first World Series, their manager did not want to stand still. He led a return to the field, a curtain call, for his players. He did the obligatory thing on the platform for the network cameras. He kept walking around the dressing room, shaking hands, hugging family, huddling quickly with some players.

Dallas Green did, however, find time for a brief chat with Carter. It was part humble and part, well, Dallas Green.

After about five minutes of waiting, the President came on the line. The manager seemed to do most of the talking. "Well, thank you, Mr. President," he began. "I tell you, we've waited a long time in Philadelphia. A lot of people thought this baseball team couldn't do it. But I think we proved that we are the best baseball team in America.....

"Thank you. I hear you're more of a football buff than a baseball guy. But we'd like to turn you around in Philadelphia. Come up, and we'll teach you to play ball.... Thank you. I'll pass the word on to the players."

It remains to be seen, of course, in 1 what capacity Carter gets the Dallas Green grind-it-out baseball lesson. And it still remains to be seen in what capacity Green gives it.

Last night, after the Phillies' 4-1 triumph over the Royals in Game 6, the win that put the Phillies on top at last, Green repeated his desire to give up the job he has held for just more than a year and move upstairs in the organization. That was his wish, he had said, if the Phillies won the World Series.

Asked if he still wanted to give up the manager's position, Green replied: "If I can."

Then he elaborated, or elaborated as much as anyone could in the rush of the winners' dressing room.

"I don't want to put up with another year like this year," Green said. "But I'll do what Paul (Owens, the general manager) and Ruly (Carpenr ter, the owner) want. We haven't talked one iota. And right "now, I just want to savor this night."

In other words, he seems to be leaving the door to that office open.

"As far as I know, he will be back," Owens said. "In all sincerity, we haven't talked about one thing. I'm about three weeks behind in that kind of work because normally, at this time of year, I'm eliminated. Outside of a briefing I had with my two field men yesterday, I've got nothing going."

"I don't think Dallas will retire," said Larry Bowa, dripping with beer and champagne. "I think he will do the job that they (Carpenter and Owens) want him to do: A lot of the stuff he said... it's not the kind of stuff you go home and lose sleep over. He's like me. He just says stuff."

And so the Greening of the Phillies was never easy. It began when Green took over for the easy-going Danny Ozark as the lost season of 1979 was running out.

"I loved Danny, as you know " Owens was saying as the club that he built celebrated, "and he did an outstanding job for me.' But I just thought we had to have a change, and that hurt me – hurt me down deeply. But Dallas came in and did a heckuva job, and he did it with strength. That's what had to be done here."

He did it his way, as they say. This old ham-and-eggs pitcher kept his pitching staff content, to be sure. But his shouting and so forth, his my-way-or-the-highway attitude, his fondness for criticizing players in the media, did not bring a lot of warmth his way.

"We struggled at first," Green said. "But then we pulled together and started winning the close, tough ball games. We stopped the in-fighting and the bickering and pulled together."

Dallas Green had some problems with Larry Bowa, the shortstop who had such a fine Series at the plate.

"It was my fault," Bowa said last night. "April, May, June, July – those months were my fault. It wasn't Dallas' fault. It was my bad mental discipline."

When last night's game was over, Green went up to Bowa and told him, "You're a winner."

"I am a winner," Bowa said later. "I'll be the first to admit that I say things I shouldn't say. But I say what I feel. Twenty-five guys wanted to say something about the fans (booing) after that Chicago game – so I said it."

Dallas Green had some problems with Garry Maddox, the centerfielder who had such a stormy final week of the regular season.

But when the season – the World Series – was over, Garry Maddox was talking about Dallas Green and that "We, Not I" sign in the clubhouse.

"That's the way it turned out," Maddox said. "If he can make us world champions, he has got to be doing something right."

At last, a season in the sun – but it was after a long, dark history

By Allen Lewis, Special to The Inquirer

It began, fittingly for Philadelphia, during America's Centennial year. It was also the year that Custer lost a unanimous decision to Sitting Bull. There weren't as many stars on the flag, as many people in the city.

In the years since 1876, 99 times a Philadelphia National League team has started a season in search of a championship, any championship. In only six of those 99 years has a title been won, any title.

In 1980 – four years after the Centennial of the Centennial- the Phillies have won it all.

The first Philadelphia National League team, the 1876 Athletics, didn't even finish the season. They were expelled for refusing to make their last western trip, and didn't return until 1883 as the Phillies.

The first team finished seventh, the second finished eighth, and that was not an unusual resting place in the years to follow, although they finished in the first division 13 times before 1900.

Despite sluggers such as Ed Delahanty and Sam Thompson in the 1890s, the closest the Phillies ever came to winning a pennant before 1915 was in 1887, when they finished 3½ games back.

Finally, in 1915, led by slugger Gavvy Cravath and one of the great pitchers of all time, Grover Cleveland Alexander, the Phillies won the pennant, won the first game of the World Series here, and promptly lost the next four to the Boston Red Sox.

The Phillies had finished sixth in 1914, but manager Pat Moran drove them to the pennant in his first season, and to second place in 1916 and 1917. He was fired when they sagged to sixth in 1918. From then until 1949, the Phillies finished in the second division every year except 1932 when they finished fourth.

For most of those lean years the ownership was as shaky as the team. Alfred J. Reach, the sporting goods manufacturer, and John Rogers owned the club from 1883 through 1902. Until the Carpenter family bought the club late in 1943, there were 10 different owners in the intervening years, with former New York police commissioner William F. Baker in charge from 1913 until his death late in 1930.

With Bob Carpenter running the team, the Phillies began to build, in contrast to the penny-pinching operation that had been the norm for years.

In 1949, the Phillies finished third; in 1950 a young team known as the Whiz Kids surprised by winning the pennant, beating out Brooklyn on the season's final day on a 10th-inning home run by Dick Sisler. This team, managed by former college professor Eddie Sawyer, featured pitchers Robin Roberts, Curt Simmons and Jim Konstanty, and players such as Richie Ashburn, Del Ennis, Granny Hamner, Willie Jones and Andy Seminick.

The Whiz Kids lost the World Series in four games to the New York Yankees, but more pennants seemed sure to follow. They didn't, and a third-place finish in 1953 was the team's best showing until 1964.

Managers came and went in that period until Gene Mauch took over after the 1960 opener. The Phillies finished last from 1958 through 1961, a year when they set a modern record by losing 23 straight games.

Mauch and general manager John Quinn were building, however, and the Phillies jumped from seventh to fourth by 1963, and were on their way to the pennant in 1964 when disaster struck.

In the greatest late-season flop in baseball history, the Phillies went into the final two weeks of that season with a 6½ game lead. The team that featured pitchers Jim Bunning and Chris Short, and sluggers John Callison and Richie Allen had only 12 games left, but lost the first 10 of them to finish in a tie for second.

It was more than a decade before the Phillies came that close again. Finally, in 1976, with the leagues having been divided into two divisions in 1969, the Phillies won the Eastern Division title under manager Danny Ozark. They did it again in 1977 and 1978, and each year they lost the championship series that decided the pennant. They lost three straight to Cincinnati the first time, and bowed to Los Angeles the next two years in four games.

A slide to fourth place resulted in Dallas Green replacing Ozark late last season, and the former pitcher drove the team to the 1980 division title in what evolved into battle with Montreal, then to the pennant in a wild five-game series with Houston.

Then came the World Series against the Kansas City Royals. And now the Phillies- more than a century after that first games and with the same nucleus as in 1976- have done it all.

Carlton, Tug KO Royals

Schmidt Series MVP

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

They have had to live with the ghosts of 105 awful seasons, seasons that didn't end this way.

To win it all, the Phillies didn't have to beat just the Kansas City Royals. They had to shake off 1915 and 1950. And '64 and ‘77. And a hundred other teams that never had a chance to blow it.

They had to demolish a whole legacy of failure in one crazy month. And they did it.

They did it that long, wet Saturday in Montreal. They did it the madhouse weekend in Houston. And, last night, they finished the job at the Vet.

They finished it with a 4-1 victory over the Royals in the sixth game of the World Series. They finished it with Tug McGraw pumping one more strikeout past Willie Wilson with the bases loaded. They finished it with police all over the field and 65,000 people screaming, "We're No 1!"

They had won the World Series. Look at that line over and over if you want. It won't change. The Phillies finally won. one. They blew the ghosts away.

"This, is truly monumental," McGraw said. "This is the proudest I'll probably ever be able to be as a baseball player, and certainly since I've been with the Phillies.

"The way September went, and the way the playoffs went, and the way the Series went, I've never been more proud to be a professional athlete in my life."

Steve Carlton was the guy who made this last win easy. He was the Carlton they needed. He threw an overpowering seven-strikeout three-hitter for seven innings, and they built him a methodical 4-0 lead.

Series MVP Mike Schmidt knocked in two with a single in the third. Lonnie Smith ran his way to a run in the fifth. Larry Bowa and Bob Boone, two guys who turned around their seasons with great Octobers, combined for the fourth run in the sixth.

All Carlton had to do was close it out, get six more outs. It sounds so easy. But they would be six long, tough, agonizing, typically Philadelphian outs.

Carlton couldn't get them. John Wathan started the eighth by battling and battling until Carlton walked him. Jose Cardenal, he of the fatal strikeout that ended Game 5, lined a single to left. Out hopped Dallas Green, who sent for McGraw, the man who has finished all the big ones for him.

McGraw got Frank White to foul to Pete Rose for one out. But he walked Wilson to load the bases, and U.L. Washington got the Royals a run with a sacrifice fly.

Next came George Brett. And a game is never over as long as he has a bat in his hands. McGraw had struck him out twice Sunday. You had to figure the odds were not with him this time.

They went to 1-and-2. Brett bounced one to deep second. But Manny Trillo was playing Brett in short right. He got there. But Rose had to race back to the bag, and here came Brett. They got there simultaneously. Ump Harry Wendelstedt called Brett safe.

So the bases were loaded a second time. Now the largest baseball crowd in Pennsylvania history (65,838) was getting nervous. Those ghosts live in all of them at times like this. McGraw threw three straight balls. You had the feeling the cardiac ward might get awfully busy in a few minutes.

But McRae took a fastball for one strike. He lofted a foul beyond first that Rose chased right up onto the rolled-up tarpaulin. But it fell into the picnic area for strike two. McRae fouled off another. And another. Finally, he grounded to Trillo. McGraw patted his heart gratefully. There were three outs left.

They took the field for the ninth, and it looked the same as always – Rose flipping the ball around the infield. Bake McBride playing catch with Warren Brusstar in right, John Vukovich catching McGraw until Boone was ready.

But there had never been an inning like this. This was 10S years of waiting. Not one fan was sitting. Most were clapping. Some were bursting with energy they didn't know how to control. You saw them jumping up and down in front of their seats. Police sat on the dugout watching them. Even they understood.

Famous Amos Otis led off the ninth. He looked at strike two and glared at ump Nick Bremigan. McGraw came back with a screwball. Bremigan paused a moment. Then he stuck a hand in the air. Two outs left.

But this was still the Phillies. It is never easy. Even winning the World Series could not come easy.

"In the eighth I felt in control," McGraw said. "I still felt all right after warming up in the ninth. But after the first batter, I began to feel very tired. I was just trying not to overthrow, just trying to throw strikes. I was trying to let them hit the ball and let my defense work for me."

But McGraw ran a full count on Willie Aikens and walked him. Wathan bounced a base hit into right. And Cardenal paced to the plate again as the Vet populace fell into an anxious silence. Nobody had to read this group's minds.

The count went 1-and-2, then 2-and-2. Foul ball. Cardenal strolled around. McGraw slammed the ball into his glove nervously one, two, three, four, five, six times. Cardenal lined a single to center in front of Garry Maddox. The bases were full a third time.

They called him Grand Slam McGraw a year ago. You were not supposed to remember that now. You couldn't help it. But White popped the first pitch foul, in front of the Phillies' dugout. Boone and Rose converged. Boone took over. It was his.

But even this out would not be routine. The ball fell into Boone's glove. Then, as he closed his bare hand on it, the ball popped away. But Rose was right with it. That is why he is Pete Rose. He stuck out his glove. The ball dropped into it for an incredible second out.

"Oh yeah, we practiced that play last week," Rose grinned.

You knew they would win it then. Wouldn't they? McGraw looked at Wilson. He decided he had one more batter left in him.

He got one strike on Wilson, looking. The Kansas City bullpen started heading for the dugout. Then a second strike on a foul tip. People were roaring, moaning, screaming. Fists were pumping into the air.

Then McGraw threw a ball, with the crowd stomping and people shrieking and police leading German shepherds around the warning track.

McGraw smoothed the mound, looked for the sign, fired. Wilson missed it, McGraw and eight other guys jumped in the air. The Phillies were world champs, friends. Believe it or not.

"All of a sudden, I felt real tired," McGraw said of that moment, the last pitch thrown, 30 guys in pinstripes running toward him.

"I was glad everything was over with. Then I looked and I saw dogs and horses everywhere. I wasn't too afraid of that. But then I saw Mike Schmidt coming at me, and I said, 'I'm not gonna be able to catch him.'"

But he managed somehow. That was how it was all night. From Carlton's first pitch, it was bedlam. It hardly seemed like a baseball game. But they managed to play it somehow.

Carlton gave indications right off that he had exceptional stuff. He fanned Wilson and Washington with crackling fastballs for the first two outs. He had a great one all night. He buzzed through three hitless innings, and you knew it wouldn't take much.

They got all they needed in the third. Royals starter Rich Gale was gone before he had gotten an out in the inning. Not all of this was Gale's fault, though. He walked Boone on four pitches leading off the inning. But then he got Smith to bounce to White at second, and White flipped to Washington for what looked like a routine force on Boone.

But Washington cheated taking the throw, and ump Bill Kunkel chose this occasion to play it by the book. He called Boone safe.

So White got an undeserved error, and Rose, the next hitter, was bunting. When the count got to 3-and-1, Brett came to the mound and told Gale the bunt rotation play was off.

But when Rose bunted the next pitch toward third, Gale didn't charge it. So Brett, who had backed up to the bag to cover, had to race in and barehand it. Rose got to first before the throw did, and the bases were loaded.

The hitter was Schmidt, and he strolled to the plate amid a din that probably could have been heard in Asbury Park. Clearly, this crowd -sensed that this could be it.

It was. Schmidt took a ball, fouled one back, then lined a fastball to right-center for what looked like an automatic two-run single. Trouble was that Smith hadn't suffered his daily case of Fall Down Disease yet. Boone trotted in with one run. But Smith barreled around third, got two steps beyond the bag and fell flat on his posterior. It looked like crisis time, because Rose was already on his way to third and Smith had no choice but to head for the plate. But the Royals didn't notice until it was too late, Smith scored, and Schmidt had his seventh RBI of the Series.

Renie Martin came on and kept it at 2-0. But the Phillies got to him in the fifth, all because of Smith and those incredible racehorse legs.

Smith led off the inning with an ordinary rope to left-center and turned it into a double.

This was just what the Royals had done to the Phillies in Game 4. Now the Royals were finding out that it didn't feel so hot the other way around.

The Phillies turned it into a classic grind-it-out run. Rose flied to deep-enough center that Smith could tag and zoom into third, and the infield marched in as Martin worked ever so carefully to Schmidt.

Martin nibbled, Schmidt stayed patient and the duel turned into a walk. Exit Martin. In came the reluctant reliever, lefthander Paul Splittorff, to face McBride.

McBride dribbled one off the end of his bat toward short. Washington had moved back, looking for the double play, so he had to make a fabulous charge play just to get the out at first. But Smith scored, and it was 3-0.

An inning later, it was 4-0. Bowa doubled with two out, Boone lined a Splittorff curve into center, and another run went up there. The rest was up to Carlton, and the way he was going, four runs looked like 40.

He allowed only three ground-ball singles over seven innings – by Washington in the fourth, by Wathan in the fifth and by Brett in the seventh. Only one Royal had passed first.

The outs kept ticking down, the cheers grew louder and maybe, just maybe, the impossible wasn't so impossible after all.

In the end, Carlton couldn't go nine. And McGraw didn't make it easy. But the Phillies won the World Series. They blew away those ghosts.

For the victors, there's a parade today

Rain or shine, Philadelphia today will celebrate the Phillies' first World Series championship with a parade through Center City and South Philadelphia and festivities at JFK Stadium.

The parade will begin at 11:30 a.m. at 18th and Market Streets and move east to City Hall, around City Hall to Broad Street and then south to the stadium, where the official ceremony will begin at 1 p.m. There will be no charge for admission to the 103,000-seat stadium, which will open at 9 a.m. to accommodate the fans.

Hero Schmidt: Amid storm, calm

By Lewis Freedman, Inquirer Staff Writer

Mike Schmidt was the eye of the hurricane.

As the champagne sprayed off ceilings, walls and people, his thick brown hair stayed dry. His right fist grasped a bottle of bubbly, but he didn't drink often from it or spill it on a teammate's head.

The Most Valuable Player in the 1980 World Series, the man who drove in the winning runs in last night's sixth-game, Series-clinching, 4-1 victory over Kansas City, was probably the least demonstrative Phillie in expressing his joy at the team's first world championship.

It was Schmidt, the third baseman who hit 48 home runs and drove across 121 runs during the regular season to lead the National League in both categories, who stepped to the plate in the third inning last night with the bases loaded and singled sharply to right, scoring Bob Boone and Lonnie Smith with the only runs the Phillies needed.

It was his eighth hit of the Series (he hit safely in every game) and his sixth and seventh RBls. And it was the tonic the Phillies needed then.

"I can't think of one bigger than that," said Schmidt, when asked to compare it to any other hit he's ever had.

Schmidt didn't even think he was outstanding in the Series, but he called winning the MVP "a great thrill."

"It could have gone to any number of guys on our team. My performance didn't stand out. I just did something every game."

When Schmidt first entered the already delirious clubhouse five minutes after the end of the game he had a blank look on his face and couldn't even react to his feelings.

"I'm still sort of in a coma," he said. And he looked it, not even smiling as people congratulated him.

When Manager Dallas Green raised the championship trophy high and shook it he yelled, "Look at this, Schmitty!" And the first smile appeared on Schmidt's face as if only then did he realize he was a member of the world champions.

The Phillies have come from behind almost every time they have won a big game lately, but the feeling on the bench was different this time, infielder John Vukovich said, and when Schmidt got his clutch single to put Philadelphia ahead, it was expected.

"This ball club was ready to win today from 3:30 on," said Vukovich. "We expected to go out and take the lead tonight and the way Lefty (Steve Carlton) was throwing, we felt Schmitty's hit would be enough."

If Schmidt didn't think his six-game show was the Most Valuable Performance, his teammates certainly did.

"I thought he was a little bit nervous at first," said Del Unser. "But then he came on and kept stroking the ball. Then he was beautiful. He gets the big hit tonight. He did it when we needed it. He's just been super."

Schmidt was on the three Phillies teams that won division titles in the 70s and always found a way to lose the pennant. So even though he had put the team ahead and Carlton was pitching shutout ball, he never let himself think ahead and picture victory.

He didn't think Philadelphia would win "until after the last pitch," he said. "I didn't want an ounce of overconfidence."

For Schmidt, 31, from Dayton, Ohio, and a Phillie since 1972, it has been a dreamlike season – with only one disappointment. His grandmother, Viola Schmidt, died Sept. 26.

"She was the first person to throw a baseball to me," Schmidt said. "That was the only prayer of mine that wasn't answered down the stretch."

It should have been one of the happiest moments of his life, but Schmidt's excitement was restrained. He was reflective, about his grandmother's passing, his faith in God ("I play this game to glorify God, to tell you the truth.") and the image of the Phillies as a team that is uncommunicative, unlikable and one that can't win the big ones.

"I don't think anyone would dislike me personally if they spent enough time with me," Schmidt said.

"The real image of the Phillies? Let me see." He struggled, then gave up. "You can write a book on the subject."

There was only one image he could make out clearly.

"People are looking at the world champions," said Schmidt. "The magazines (writers) are going to come to Clearwater first next spring. People will be watching us and what we do. That's a good feeling."

And Mike Schmidt smiled, broadly. At last he looked like he was enjoying himself.

How others view this World Series

John Schulian, Chicago Sun-Times:

"In a city that has spent a lifetime living on losers and boos, the Phillies of 1980 were the inevitable product – crass, grouchy, sullen and almost malevolently single-minded. Their manager, an old knockdown pitcher named Dallas Green, whipped his bitchy troops into shape by telling them he was so tight with the front office that they couldn’t get him fired."

Bill Sullivan, Austin American-Statesman:

"For seven innings Tuesday night it was dull and predictable, a routine ending to a World Series that had been anything but routine. But somehow you knew it could not end that way. After five exciting, gut-wrenching games, this Series could not end without some final touches of high drama, and it could not end without Tug McGraw."

Phil Pepe, New York Daily News:

"For 98 years they have played this game, this little boys' game that has made men rich, made them famous, made them laugh, made them cry, made them fight, made them act like kids. For 98 years, the Phillies have suffered through defeat and disappointment, through failure and frustration, through condemnation and ridicule, and never in those 98 years, not ever, have the Phillies reached the heights, the joy, the moment of exultation they climbed at 11:29 Tuesday night.

"No more Philadelphia jokes. The Phillies are World Champions at last.

"They did it with power and pitching. They did it by coming from behind in three playoff games against the Astros, and in three World Series games. And they did it with a get-tough manager, Dallas Green, who did it his way, who adhered to a philosophy of 'no sonufabitch but me is going to run that thing….

Bruce Keidan, Pittsburgh Post Gazette:

"There are, by actual count, 15 adult males in the United States who have no wish to give up their own jobs and become the manager of a major league baseball team. Seven of those are recent emigres from Bangladesh. Seven more are photographers for Playboy magazine. The other one is Dallas Green.

"Surely there must be worse jobs; milking rattlesnakes for instance, or cleaning up after the elephants. But there have been times since he took over the Phillies that Green has thought seriously about the beauty of doing any job other than the one he has been assigned. 'I never considered quitting,' he said, 'because I've never quit anything. That's just not my nature.'"

Thomas Boswell, Washington Post:

"In this 77th Series... the focus of pitching attention has not been on the starters nearly as much as on the finishers. In every game, the key hurling figure has been either Phillie Tug McGraw or Royal Dan Quisenberry, whether they were winning the game, saving the game or getting crushed in defeat."

Jerry Izenberg, New York Post:

"Brothers and sisters, we have now moved the tournament back to Philadelphia, back to where the hungry lions haven't even had a nosh during a World Series diet which has lasted more than three-quarters of a century. The eyewitness chroniclers of the home side's two and only World Series appearances (there were no titles) have long held the status of tribal witch doctors, spinning tales of mystical roots before a lonely camp-fire.

"And now they are coming together men, women, children and the family attack-parakeet down the expressway and out to Veterans Stadium... vocal chords at the ready... an a cappella chorus to bear witness to the end of the world. Oh, Lord, if the Philadelphia Phillies finally seal away a World Series championship on this frosty October Tuesday, there would seem to be nothing else to do but cancel Wednesday for lack of interest."

Mike McKenzie, Kansas City Times:

"It is known as the Fall Classic. When it is classic, there is no loser. One team prevails. One does not. Neither hangs heads.

"The World Series just concluded to the Phillies' advantage – 4 games to 2 – was not a classic. The Phillies showed classic lines throughout. The Royals did not, only brief flashes. From Kansas City's point of view, it will always be said of this first Royals' World Series, beating the Yankees to get there was satisfaction enough, that the heart went to sleep after a playoff celebration in New York and the bats and feet and arms and heads followed."

David Israel, Chicago Tribune:

"After 97 years, the Philadelphia Phillies were entitled. They had been waiting for this longer than any team ever to punch the clock and don flannels or doubleknits for work. Tuesday night, they pulled out the stopper, had a whopper, and just hoped that someone would get them to the parade on time Wednesday morning."

It was a time to rejoice… a time to forget

By Frank Dolson, Inquirer Sports Editor

So this is what it's like.

So this is how it felt to be a Pirate fan in 1960 when Bill Mazeroski hit the ninth-inning homer against the Yankees, or a Mets fan in '69 when the Orioles fell in five, or a Reds fan in 75 when Joe Morgan's two-out hit in the ninth beat the Red Sox, or a Pirate fan in 79 when Willie Stargell destroyed the Orioles.

So this is the feeling Phillies fans, and Phillies players, and Phillies management have been waiting all these years, all these decades to experience.

It's agony turned to ecstasy as a towering, bases-loaded foul in the ninth pops out of the glove of catcher Bob Boone... and into the glove of first baseman Pete Rose.

It's 65,000 people standing at their seats, in the aisles, surging forward, then stopping again, holding their breath as Tug McGraw plays out yet another late-inning drama.

It's the sound of cheers, of unbridled joy sweeping through Veterans Stadium, rising high above South Philadelphia – made all the more beautiful, all the more meaningful because of the long years of boos, of frustration, of disappointment that preceded this night.

It's watching Larry Bowa, capless, dancing off the field with short, mincing steps, a look of little-boy jubilation on his 34-year-old face, the dream of a lifetime finally reality.

It's the sight of Paul Owens, the builder of this Phillies team, a flood of tears streaming down his face, and Dallas Green, the driving force behind it, locked in a long, passionate embrace.

It's people remaining in the stands, long minutes after the final out, eager to squeeze every last minute of happiness out of this night, reluctant to leave this place, this scene, this moment behind.

It's members of the ground crew hugging each other near home plate as white-helmeted police, some with German shepherds, others on horseback, guard the bright green Astro-Turf.

It's the roar of delight as Kevin Saucier, one of the youngsters on this team, rushes back onto the field, holding a bottle of champagne over his head and touching off another wave of emotion.

It's Pete Rose, a kid of 39, reappearing moments later, also armed with the drink of champions, waving to the crowd, his face every bit as happy as it was that night at Fenway Park in 75 when, as a member of the Cincinnati Reds, he celebrated his first world championship.

It's Tug magically transforming a moment of supreme tension into a sigh of relief and a smile, getting out of a bases loaded jam in the eighth and patting his left hand against his heart, again and again and again.

It's seeing a team that wasn't supposed to be good enough to win, a team that wasn't supposed to care enough to win, turn itself into the best baseball team in the world under the most testing of circumstances.

It's hearing and feeling the love and the pride of a city directed at a group of athletes who, in the last three, incredible weeks, changed the image of the Philadelphia Phillies from a team that can't win the big one to a team that kept winning all the big ones.

It may have taken this Phillies team a long time to find itself and to truly believe in itself, but that belief stood out in bold relief these last few giddy days.

It was a belief that prompted Bowa, the emotional, wound-up-as-tight-as-a-clock shortstop, to confront a radio man in the clubhouse after Sunday's ninth-inning victory and tell him, "You said yesterday the magic was gone, didn't you? Well, it's not magic. We've got a good baseball team. People still don't realize that. I guess until we win they won't say we have a good baseball team. There ain't no magic about this team. Not when you get base hits like Mike Schmidt does and throw out runners like Manny Trillo does and get pitching like Tug McGraw does. That's not magic. That's good baseball."

And last night, as a nation watched and a city of sports-lovers rooted, the 1980 Phillies did what the 1915 Phillies, the 1950 Phillies, the 1964 Phillies, the 1976-77-78 Phillies couldn't do: they fulfilled the expectations of their most demanding, most starry-eyed fans.

They didn't do it easily; this team has never done anything easily. Even with Steve Carlton on the mound, a four-run lead and two innings to go, it wasn't easy.

Even after McGraw got Hal McRae to bounce a 3-2 pitch to Trillo with the bases loaded in the eighth to the vast relief of the assembled throng, it wasn't easy.

There were still three outs to go – the three biggest, toughest, most important outs any Phillies pitcher was ever asked to get.

"I was running out of gas," Tug would say later, but even a McGraw pitching on heart alone was equal to the task.

What an eerie feeling it was to see this much-maligned Phillies team take the field in the top of the ninth with the world championship in sight, the crowd on its feet, police everywhere – on both dugouts, down the right and left-field lines, a pair of helicopters overhead, one hovering over left field, the other lazily circling the stadium.

McGraw threw a third strike past Amos Otis and one of the policemen atop the third base dugout held up his hand and waved off a kid in a red jacket who had started to bolt toward the field. "Lord, this is heaven," said the message on the scoreboard.

Not yet, it wasn't. As spectators, young and old, jammed the aisles behind both dugouts, there was a walk, then a single, then another single.

At that moment – 11:25 P.M. – a brief hush fell over the crowd. It took no great ability to read the minds of the 65,000. "My God," they were thinking, "is it going to be snatched away again?"

Not this year. Rose clutched the foul pop that bounced off Boone's glove and the Phillies were one out away; so close to the realization of their dream that more police arrived on the scene, moving in from both bullpens, accompanied by their dogs.

Now it was 11:28 and Tug was one strike away and the only people in the place not standing were the cops sitting on top of the dugouts.

McGraw threw; the crowd edged forward, then pulled up again. The pitch was high.

Again McGraw threw, and Willie Wilson swung... and the din was deafening.

It was 11:29 p.m. on Tuesday night Oct. 21, 1980, time to forget the agony of 1964, time to stop talking about blowing 6½ game leads with 12 games to go, and losing a playoff game because a fly ball wasn't caught in left field in 77, and losing another playoff game after a line drive wasn't caught in center field in 78.

It was time to sing the praises of the world champion Philadelphia , Phillies. As somebody in the press-box said, if you live long enough, you see everything.

Phillies kings of baseball

Carlton, Tug KOs Royals; Schmidt Series MVP

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

They have had to live with the ghosts of 105 awful seasons, seasons that didn't end this way.

To win it all, the Phillies didn't have to beat just the Kansas City Royals. They had to blow away 1915 and 1950. And '64 and '77. And a hundred other teams that never had a chance to blow it.

They had to demolish a whole legacy of failure in one crazy month. And they did it.

They did it that long, wet Saturday in Montreal. They did it that madhouse weekend in Houston. And, last night, they finished the job at the Vet.

They finished it with a 4-1 victory over the Royals. They finished it with Tug McGraw pumping one more strikeout past Willie Wilson with the bases loaded.

They finished it with police all over the field and 65,000 people screaming, "We're No. 1!" They had won the World Series. Look at that line over and over if you want. It won't change. The Phillies finally won one. They blew the ghosts away.

Steve Carlton made this easy. He was the Carlton they needed. He threw an overpowering three-hitter for seven innings while they built him a methodical 4-0 lead.

But Carlton started the eighth with a walk and a single, and Dallas Green sent for McGraw, the man who has finished all the big ones for him.

He got Frank White to foul to Pete Rose. But he walked Wilson to load the bases, and U.L. Washington got the Royals a run with a sacrifice fly. Next came George Brett, and a game isn't over as long as he has a bat in his hands.

He bounced to Manny Trillo in short right. Brett and Rose raced for the bag. They got there simultaneously. Ump Harry Wendelstedt called it a hit.

So the bases were loaded a second time, but Hal McRae grounded to Trillo. There were three outs left.

Famous Amos Otis started the ninth by looking at strike three. But it was not going to be that easy. Willie Aikens walked. John Wathan bounced a base hit to right. Jose Cardenal lined a single to center in front of Garry Maddox. The bases were full a third time.

They called him Grand Slam McGraw a year ago. But not this year. White popped the first pitch foul, in front of the Phillies' dugout. Bob Boone and Rose converged. The ball fell into Boone's glove. And out of Boone's glove. And into Rose's glove for an incredible second out.

You knew they would win it then. McGraw got one strike on Wilson looking. Then another on a foul tip. Then one ball, with the crowd standing and people screaming and police leading German shepherds around the warning track.

McGraw smoothed the mound, looked for the sign, fired. Wilson missed it, McGraw and eight other guys jumped in the air. The Phillies were world champs, friends. Believe it or not.

It was only a baseball game. You had to keep telling yourself that, because it didn't feel like a baseball game at the beginning. It was hard to say what it did feel like. Buy everybody knew it wasn't the first of three games with the Cubs in June, that's for sure.

There were 65,838 people crammed into the Vet, waiting to explode. But it was tough to tell whether they really wanted to bother playing this thing out or whether they just wanted to have the teams run out on the field and then have somebody declare the Phillies winners. It hardly seemed to occur to anybody except the people playing that the Series wasn't over.

"The only questions in Philadelphia," laughed George Brett before the game, "are, 'How bad is the stadium gonna be when they win?' and 'When does the parade start?' But hey, it doesn't bother me."

The managers, at least, were aware of the possibilities. The Royals' Jim Frey was a coach with the Orioles last year. The Orioles, of course, also came home for the sixth game, leading , three games to two. They had the reliable arms of Jim Palmer and Scott MacGregor ready to pitch.

"They were already building platforms for the politicians in Baltimore," Frey said.

But they didn't get to use them, because the Orioles lost two in a row, as you might recall.

Dallas Green also seemed concerned that people might be ready to launch the parade prematurely.

"We're one game away, I know," Green said. "But we were two games away many moons ago, weren't we? We've still got to win one out of two. When we do that, then we'll walk down Broad Street and Market Street. Then we'll have some fun."

But this crowd was ready for fun right now. It was quite the scene at 6:30 p.m. when the gate opened in the right-field corner and out marched row after row of uniformed police. It looked like the troops marching into Paris. Was this really just a baseball game?

The fervor built through the pre-game introductions, and the volume level as Carlton went out to pitch the first was unlike anything ever heard at the Vet. Carlton proceeded to fan the helpless Willie Wilson (Wilson's 10th strikeout of the Series), and it was bedlam clear into the bottom of the first.

Carlton gave indications right off that he had exceptional stuff. He fanned U.L. Washington on a crackling fastball for the second out. Brett hardly had a decent swing before be bounced a 1-2 pitch to second. Watching that inning did not serve to calm anybody down.

The tumult continued as Lonnie Smith grounded out to start the Phillies half of the first. Finally, Pete Rose stroked a one-out single between short and third for the first hit. Suddenly, it felt like a ball game again instead of New Year's Eve.

Writers were organizing pools before the game to figure out how long Royals starter Rich Gale would last. It wasn't long.

Gale was out before he had gotten an out in the third inning. The only faster exit by a starter in the Series was Larry Christenson's five-batter show in Game 4.

Not all of this was Gale's fault, though. He walked Bob Boone on four pitches leading off the inning. But he got Smith to bounce to Frank White at second, and White flipped the ball over to Washington for what looked like a routine force on Boone.

Washington had cheated a little. But he wasn't exactly the first shortstop in history to do that. Ump Bill Kunkel thought the cheat was so flagrant, though, that he called Boone safe.

That delighted Washington and Frey, naturally. But how do you argue when you've clearly cheated? Your only case is that nobody ever calls it. Kunkel wasn't buying that one.

So White got an undeserved error, and the Royals had to figure out whether Rose, the next hitter, was bunting and how to play it. Rose squared twice and took two balls. Out charged pitching coach Billy Connors. Then out stomped Green, claiming Frey already had visited the mound once when he was arguing with Kunkel.

Gale was allowed to hang around, but it was just as well for the Phillies. Rose swung away on the 2-0 pitch and fouled one back. Then he squared again and took ball three.

Brett came to the mound and told Gale the rotation play was off. But when Rose bunted the 3-1 pitch toward third, Gale didn't charge. So Brett, who had backed up to the bag to cover, had to race in and barehand it. Rose got to first before the throw did, and the bases were loaded.

Mike Schmidt strolled to the plate amid a din that probably could have been heard in Asbury Park. Clearly, the crowd sensed that this could be it.

It was. Schmidt took a ball, fouled one back, then lined a fastball to right-center for what looked like an automatic two-run single. Trouble was that Smith hadn't suffered his daily case of Fall Down Disease yet. Boone trotted in with one run. But Smith barreled around third, got two steps beyond the bag and fell flat on his posterior. It looked like crisis time, because Rose was already on his way to third and Smith had no choice but to head for the plate. But White, the cutoff man, had conceded the two runs and set up at second, so Jose Cardenal, the rightfielder, didn't even look at the plate, threw it to Washington between second and third, and Smith scored.

That ended Gale's postseason, and on came Renie Martin to see if he could keep it from getting worse than 2-0. He could- in seven pitches. He got Bake McBride to foul out to White, Greg Luzinski to line one right at Brett and Garry Maddox to fly to Cardenal. So it was still a game.

But the Phillies kept inching away. Martin ran into trouble in the fifth, all because Smith has those incredible racehorse legs. Smith led off the inning with an ordinary rope to left-center and turned it into a double.

This is just what the Royals had done to the Phillies in Game 4. Now the Royals were finding out that it didn't feel so hot when it happens the other way around.

The Phillies turned it into a classic grind-it-out run. Rose flied to deep-enough center that Smith could tag and zoom into third, and the infield had to march in as Martin worked ever so carefully to Schmidt.

Martin nibbled, Schmidt stayed ever so patient and the duel turned into a walk. Exit Martin. In came the reluctant reliever, Paul Splittorff, to face McBride.

They got to 2-and-2. McBride dribbled one off the end of his bat toward short. Washington had moved back, looking for the double play, so he had to make a fabulous charge just to get the out at first. But Smith scored, and it was 3-0.

An inning later, it was 4-0. Larry Bowa doubled with two out. Boone lined a Splittorff curve into center. The rest was up to Carlton, and the way he was going, four runs looked like 40.

He had a no-hitter for three innings. Then Washington beat out a chopper to deep short for the first hit. But Brett bounced to Bowa, who raced to second and started his seventh double play of the Series. That's a record for any player at any position.

The one-hitter stood until the fifth, when John Wathan bounced a single through the middle with two outs. But he didn't get past first, either.

In fact, for seven innings, the only Royal who did was Amos Otis. Otis and Willie Aikens walked back-to-back with one out in the second. But Wathan bounced into the evening's first double play before that threat got too serious.

Brett got a seventh-inning single with nobody out. But he didn't move either. So the outs kept ticking down, the cheers grew louder and maybe, just maybe, the impossible wasn't so impossible after all.

Philly was hopping with Series back in town

Brett bags a beauty, Lillian likes the Phils… but why is Patti Labelle in a quandary?

Amid the usual confusion and revelry a World Series brings to a city, the Franklin Plaza hotel chose yesterday to stage its formal opening ceremonies.

So, while Kansas City Royals players and personnel wandered through the hotel lobby, biding the hours until Game 6 began, city officials and other guests – about 4,000 of them – were toasting the arrival of Philadelphia's newest major hotel.

People lurked in the lobby in search of autographs as the athlete celebrities milled, and a Mummers contingent played and strutted.

On the hotel mezzanine, revelers sipped their drinks, nibbled on shrimp, smoked salmon and steamship round of beef, and made their way around two gigantic ice sculptures, one that formed the initials "FP" and another that spelled out the full name of the hotel.

•

Big game, right? Big day in the rivalry between Philly and K.C., right? So what do the mayors of these warring cities have to. say to one another on the phone?

Mayor Bill Green slipped away from the Franklin Plaza hoopla at about 11:30 a.m. to call K.C. Mayor Richard Berkley on the house phone. Green's end of the conversation went something like this:

"Was the food good? Good. Yeah, I guess we might as well open this hotel as long as the mayor of Kansas City is staying here.

"I've got four luncheons today."

That's it. Then they said goodbye. Saving the rough stuff for game time, nodoubt.

•

When he hung up the phone after talking to the Kansas City mayor, Green waxed eloquent.

"I feel terrific today. There's a very up mood in the city. I really feel this is the one city in the country that has the chance to win it all." He mentioned the Phillies, Eagles, Flyers, Sixers.

"We've just won a Nobel prize, we have the greatest orchestra in the world…."

And that's how the mayor of Philadelphia feels on a day when his city hopes to become champion of the world.

•

Royals reserve first baseman Pete LaCock was patiently administering to autograph-seekers in the hotel lobby when something grabbed his attention.

In fact, that something was a woman, and she grabbed more than his attention. LaCock yelled after feeling the hand on his posterior, then turned to watch a woman departing quickly across the lobby. LaCock seemed startled, but not unhappy.

LaCock said he felt great after the one-day World Series layoff. As for predictions, he would only offer, "Oh, I think it'll be about 70 degrees today."

•

Peggy Duffy, 58, was thrilled when Pete LaCock signed her World Series program right across his picture.

"Isn't it exciting? Every day I come over here," said the grandmother from Olney, who was stalking players in the Franklin Plaza lobby. She works across the street, she said, at the Archdiocese food distribution program.

"Aren't they neat?" she said of the Royals. "I wish 'em luck – my husband would kill me if he heard me say that."

And the autographs, of course, are for her grandsons.

•

George Brett, the famous George Brett, who is reputed to have the same devestating effect on women he inflicts on opposing pitchers, shocked workers at the hotel's Guest Service desk when he approached them last week to ask how he could go about finding a nice girl for a date.

Susan Prinsen and Marie Porter, Franklin Plaza representatives, said they were pretty sure the rich, famous, handsome bachelor was just kidding, but they weren't sure.

"He really seemed serious, as if he had a hard time meeting girls," Prinsen recalled yesterday. Brett was advised to try Elan, a restaurant disco in Warwick.

That was last week. Brett seemed to have overcome his reticence this week, Prinsen and Porter noted. They observed the slugging third baseman in the company of an attractive dinner date Monday night.

•

Brett was wearing a red Phillies insignia in his right lapel.

"It was a gift to me last night," he explained "I thought it was a cute. little thing."

Brett was outside the Franklin Plaza signing autographs madly as he waited to go to lunch with some other players and friends, among them John Sciarra of the Eagles who, Brett said, had gone to school with the Royals' Jamie Quirk.

•

Ruly Carpenter, the Phillies president, has a $30,000 Franklin Plaza blowout planned if the team captures the World Series.

All 297 Phillies organization employees will be invited to the bash today or tomorrow, depending on the outcome of the series.

Hotel catering manager Peter Freidrich has planned a special buffet for the team, including exotic seafood, chateaubriand, imported French white wines and "a good Bordeaux."

•

A month ago, when presidential candidates Ronald Reagan and John Anderson were about to debate on national television, the local Anderson campaign folks printed up thousands of red-and-white stickers that read: "Tonight's the Night!" with Anderson's name printed in small type discreetly at the bottom.

The idea was to have campaign workers posted throughout the city at train and subway stations, slapping the stickers bn anyone who would stand still for it.

However, the debate was scheduled for a Sunday, when few people ride public transportation. Still, red and white are the Phillies' colors.

So, yesterday, the Anderson legions were on the streets, pasting their stickers on rabid fans – of the Phillies, if not of Anderson.

•

If things had worked out a little differently, country singer Charley Pride might have been playing in a World Series instead of singing the national anthem to open a Series game, as he did last night at the Vet.

Pride, once a pitcher and powerful hitter for the Memphis Red Sox of the old Negro Pioneer League, pursued a career in baseball for 10 years. He got a tryout with the California Angels in 1961, but couldn't cut it in the majors. So, he turned to cutting records – with much greater success.

"I wanted to be the greatest ballplayer that ever put on a uniform," Pride once told a reporter. "I wanted people to know that Charley Pride hit more home runs than Babe Ruth and stole more bases than anyone. I wanted every record imaginable in the game."

•

District Attorney Ed Rendell was present as the Phillies took the field last night – just as he had been for the previous five Series games. Rendell said that he wanted to be sure he ' didn't miss any memorable moments of this year's Fall Classic.

"When I was a kid in New York, I saw (only) Game 3 of the 1954 World Series," Rendell said, adding ruefully that he missed seeing Willie Mays' famous over-the-shoulder catch of Vic Wertz' long drive in Game 1 between the New York Giants and the Cleveland Indians.

•

What was a last-minute ticket to last night's game worth ?

Well, to Bobby Kutler, manager of Democratic Senate candidate Pete Flaherty's Philadelphia office, a ticket may have been worth his job.

Flaherty, sitting comfortably on the first-base side at last night's game, said he "came off the train from Lancaster in the middle of the afternoon."

"Don't ask me how, but I copped a ticket for the game from the guy next to me," Flaherty said, pointing to Kutler. "I told him he had to come up with two tickets or there would be a new man in the office in the morning."

•

Former Phillie (and now Phillies broadcaster) Tim McCarver said that he wasn't really disappointed about having left the Phillies the year before they went to the Series.

"I'm not unhappy about it," said McCarver, who went to three World Series with the St. Louis Cardinals. "I'm glad for the guys that that anvil has been taken off their shoulders."

Asked,.however, how he felt about not being able to broadcast the game, after covering the Phillies all season, McCarver said, "Horrible, horrible – dastardly!"

•

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and his wife, Louisa, a native of Villanova, stopped by the gaudy yellow-and-white NBC hospitality tent outside the Vet last night before the game. Kuhn, who said that he and his wife had spent their time in the city "hoofing around town," told a reporter that he was "impressed by the excitement in the city of Philadelphia – right from Bill Green down through everybody."

•

Predicting the outcome of the World Series is much simpler than sitting on the bench, Commonwealth Court judge James C. Crumlish observed last night from his box seat along the first-base line.

"This is easy," Crumlish said. "I wish I had them all that easy to call." He predicted a Phillies victory by four runs.

•

Back to the Royals killing time.

It seems, according to the National Park Service, that most Royals team members visited the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall before the first game of the series. But a number of the players have requested repeat tours this time around.

•

Arthur Margo of Cherry Hill staggered into Maces Crossing, 17th and the Parkway, late yesterday afternoon with an armful of Phillies T-shirts. He immediately had several buyers at $4 each.

"I've been doing this for 25 years," he said, "but I have never seen anything like this. The way these things are selling is unbelievable."

•

Marcel Brossette, owner of the La Camargue Restaurant on Walnut Street near 11th, admires Steve Carlton, and Steve Carlton admires fine wine. So, when Carton won his 10th game in the regular season, Brossette gave him a 10-year-old bottle of Burgundy. Carlton ended the season with 24 wins and, sometime after World Series fever abates, Brossette has a bottle of 25-year-old Bordeaux to add the the Carlton collection.

•

Frank Palumbo says that the singer now performing in his night club in South Philadelphia, Jimmy Darren, is in an absolute agony of ambivalence. He is a South Philadelphian who just bought a house at 11th and Morris Streets, and a rabid Phillies fan. Yet, last night, he could hardly root for his team. Darren contracted to sing the national anthem for the seventh game and couldn't decide whether he wanted national TV exposure more than a Phillies win in six.

•

The guest service desk at the Franklin Plaza has gotten some strange requests since the Royals checked in. According to guest service representative Marie Porter, one good Samaritan showed up at the counter with a special cushion he had invented – and wanted her to pass along to George Brett.

•

While the Phillies and Royals were preparing for last night's game, their wives were busy socializing with "the enemy." The wives of the Phillies and Royals got together, late yesterday morning for a sightseeing trip to Independence Hall, followed by lunch at Old Original Bookbinder's, at Second and Walnut.

The somewhat ecumenical sortie was arranged by Pat Green, the mayor's wife. The group also included the wives of Ruly Carpenter, the Phillies owner, and the team managers Dallas Green and Jim Frey.

•

The Philadelphia Orchestra played a junior student concert last night,. but that doesn't mean the famed symphonic assemblage ignored what was happening farther down Broad Street. With associate conductor William Smith leading the orchestra through a series of works – including "Instant Replay," an original modern dance number choreographed to Fasch's Sinfonia in G major – the players kept up with happenings at Veterans Stadium thanks to a handy stagehand.

Making like a third-base coach, the stagehand used a complicated series of hand signals to relay the inning-by-inning events from the wings.

(The orchestra also decided to eliminate the usual intermission, preferring to finish early so that the audience could escape Center City in case of the celebration expected following a Phillies victory.)

•

Philadelphia singer Patti Labelle found herself holding two tickets yesterday, one to Game 6 of the World Series, the other for a plane trip to Lake Tahoe.

Labelle was scheduled to open at Harrah's with that staunch, grumbling Dodgers fan Don Rickles.

The singer was complaining to anyone willing to listen Monday night at the Da Vinci restaurant at 20th and Walnut Streets that the professional engagement would have to take precedence.

She said she looked forward to getting little sympathy from her co-performer, "Mr. Warmth," who is no doubt still smarting from the defeat handed his team at the end of the season by the Houston Astros – remember the Houston Astros?

•

Ribs for lunch, ribs for dinner. Chub Feeney had only one menu item on his mind Monday at Bogart's, at 17th and Walnut Streets.

Before leaving, Feeney stopped for a chat with 76ers star Julius Erving, whom he spotted at another table.

•

Lillian Carter is as partisan in baseball as she is in politics, and her son says she's rooting for the Philadelphia Phillies to win the World Series.

"Since the Dodgers were eliminated, she's been a real strong Phillies fan," President Carter said Monday in Youngstown, Ohio, in response to a question about his 82-year-old mother. He said his mother told him when he called recently that she was too busy watching the baseball championships to talk to him.

Miss Lillian is recovering from surgery for a fractured hip in an Americus, Ga., hospital.

•

Vin Scully, who is broadcasting the series for CBS radio, must be a Phillies fan. Before he left the Barclay Hotel for Games 3, 4 and 5, he told hotel manager Bill Tremble that he would be back, unless the Phillies wrapped up the series in Kansas City.

"And I hope they do," Tremble quoted him as saying.

Also staying at the Barclay this time was baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Perhaps that accounted for the hotel's drastic break with tradition. For the first time, there was a television in the bar at the Barclay.

•

Chips, a South Philadelphia restaurant that normally closes on Mondays, made an exception this week to feed a hungry crowd of Kansas City Royals ballplayers for dinner.

"We wanted to show hospitality to the visiting team, you know," said Tom Cipollone, who owns the restaurant with his father, Vincent, Jr.

The Cipollones got a call from Eagles defensive back Frank LeMaster, who frequents the restaurant with other members of the football team. Cipollone said he enjoyed entertaining football players and was glad to make an exception this week to accommodate the visiting American League baseball champs.

Cipollone said he wasn't sure how many Royals showed up for dinner, "but (there were) a lot of them. And I'm happy to say that they all have fine appetites."

Pete Rose spent part of yesterday in the Italian Market, shopping for a jacket. He encountered a friend, Nick Perrone, owner of the Little Table, one of those little South Philadelphia , Italian restaurants. Pete promised he would drop in for a postseason feast.

•

Petey Rose is having the time of his life as bat boy for the Phillies and his famous father, but it took a court order to get him the job.

Karolyn Rose, whose 15-year marriage to Pete Rose ended in divorce in August, objected to the World Series trip because only Petey, 10 – and not the couple's daughter, Fawn, 15 – was to be included.

Rose's attorney, Douglas Cole, said that the Phillies star doesn't have facilities to take care of his daughter. Cole said Petey is sharing his father's hotel room and was welcome in the Phillies locker room.

•

Infielder Onix Concepcion is 22 years old and in his first World Series. In fact, he was just called up from the minor leagues by the Royals a couple months ago. So far, he has been used in the Series only as a pinch-runner, but he still says being in the Series is one of the most exciting things that has happened in his life.

Yesterday, signing autographs in the lobby of the Franklin Plaza, he was taking it all in stride.

"I just slept all night – 9 o'clock till 11 this morning," he said. "No, I'm not worried. I know we're going to win...."

Concepcion said he would spend the afternoon watching soap operas in his room. His favorite is "General Hospital."

•

Monte Irvin was a leftfielder for the New York Giants in the World Series in 1951 (they lost) and again in 1954 (they won). For 12 years he has worked for the commissioner of baseball. He says his job is "to do anything and everything to keep baseball the No. 1 sport."

He was at the Franklin Plaza yesterday doing that. He told a reporter ; that the World Series is the "greatest event in professional sports."

Greater than the Super Bowl?

"The Super Bowl is just one game. The World Series is a series of games. That's what makes it (the greatest)."

•

There was a man in the Franklin Plaza lobby yesterday in a three-piece purple suit. He spent the morning approaching people asking for tickets to the game.

He tried Onix Concepcion and Monte Irvin. He said he was a very close friend of Amos Otis, a Royals outfielder. He said he knew Willie Aikens, the Royals' first baseman. It earned him no tickets.

No matter. Ralph Benbow of Morrisville, Pa., achieved a measure of recognition anyway. Several women approached him for his autograph and he obliged.

One thanked him and turned away, squinting at his signature. "I knew Monte Irvin," she murmured, "but I don't know who that is."

•

Tall Rich Gale, who was scheduled to start Game 6 for Kansas City, strode through the lobby of the Franklin Plaza at about noon yesterday, pursued by autograph seekers.

He had little time for talk. He said he would spend the rest of the day resting. He said he had had dinner the night before with his in-laws, and would just as soon not talk anymore.

Gale did stop, though, to speak to three men. A reporter eavesdropped. (He was chatting about sports and about a house he is building.) Professional photographers with long lenses snapped his picture, as did amateurs with Instamatics.

A dark-haired woman, much shorter than Gale, appeared at his side. He grabbed her and said "Let's go." People pursued him across the lobby. "In a few minutes, please," Gale said, then he and the dark-haired woman, presumably his wife, disappeared.

•

Contributing to this article were staff writers Mark Bowden, Maryanne Conheim, John Corr, Lewis Freedman, Al Haas, Carol Horner, Donald Kimelman, Chuck Newman, Gary Ronberg, Jack Severson and George Shirk.

Phils stopped the runners, got the big strikeouts

By Allen Lewis, Special to The Inquirer

There were a diamond-full of individual heroes in the winning of the first world championship in the near-century the Phillies have been in existence.

Their names will be remembered as long as major league baseball is played in Philadelphia. And yet, in the final analysis, following last night's 4-1 victory in the clinching sixth game before 65,838 at Veterans Stadium, what may have swung the tide in favor of the Phillies was the ability of their pitchers to do two things – stop the running game of the Kansas City Royals and get strikeouts when they were vitally needed.

During the American League season, the Royals were known as a club that was always on the run. They showed flashes of their ability to take the extra base in their fourth-game victory, but throughout the World Series they never really got their running game going. They stole 185 bases during the regular season and that was an integral part of their offense. In the six games against the Phillies, they managed to swipe just six bases, but only once did a steal help the Royals win.

After each one of the six games, Kansas City manager Jim Frey mentioned the fact that he had flashed the steal sign numerous times but his players would come back to the dugout complaining that they were unable to get the jump necessary to attempt a steal.

In the matter of power pitching, one statistic tells the story. In six games, the Phillies pitching staff struck out 49 batters; the Royals staff fanned only 17.

What's more, in the four games the Phillies won, each ended with the tying or winning run at the plate and each ended with a Royals batter swinging and missing. In addition, in every one of the Phillies victories, two of the outs in the final inning came by the strikeout route. The strikeout superiority demonstrated one difference between the two major leagues. In the National League, power pitchers predominate; in the American League they do not.

Last night's victory was a perfect example of the pitching superiority. Starter Steve Carlton, whose move to first base may be as good as any pitcher in baseball has, had Royals runners at first base so cautious they were often moving the wrong way when the big lefthander pitched to the plate. Carlton struck out seven but didn't concentrate on strikeouts. In both the second and fourth innings, when the Phillies lead was two runs or less, Carlton got the needed ground balls that led to routine double plays.

In the tense ninth, relief ace Tug McGraw, who had wiggled out of a bases-loaded jam in the eighth, threw a called third strike past leadoff batter Amos Otis, and that was a very big out in retrospect.

Immediately after that, a walk and two singles loaded the bases, putting the tying runs on base.

The indomitable lefty then got Frank White, the Most Valuable Player when the Royals won the American League playoff series in three games from the New York Yankees, to lift a pop foul in front of the Phillies dugout. Catcher Bob Boone came over, got his glove on the ball only to have it pop out. The ever-alert Pete Rose, always it seems the right man in the right place, grabbed it with a sudden lunge before it hit the ground.

That brought up Willie Wilson, the man who collected more hits than anybody in baseball this season but who hit only .154 in the Series. An extra-base hit could tie the score but McGraw got the desperately-needed strikeout that ended the game, clinched the World Series title and enabled Wilson to achieve the unenviable distinction of striking out more times – 12 – than any player in World Series history.

There were other factors that led to the victory.

One may have been Frey's use of relief ace Dan Quisenberry too often and too soon. Unlike McGraw, who pitched in four games to Quisenberry's five, the Royals reliever is a one-pitch pitcher whose effectiveness depends almost entirely on his unusual underhand motion. The more often a batter faces him, the more likely he is to have success. The righthander lost both the second and fifth games and in each the damage was done after he had worked at least one scoreless inning.

Until last night's game, Frey had employed only five pitchers. In contrast, Phillies manager Dallas Green used his entire 10-man staff.

One other thing that could have tipped the scales in favor of the Phillies is that they were under the gun so much in recent weeks. From mid-September on, they were game after game in must-win situations, and they came from behind to win so often it gave them the feeling they couldn't lose. In contrast, the Royals coasted to their Western Division title, then breezed through the AL playoff series in three games. It may have been the worst thing that could have happened to them, and the trial by fire the Phillies underwent may have been the best thing they could have experienced.

The Phillies had one other thing going for them, too. They had a manager who wasn't afraid to encourage them when they earned it and to roast them when they required that. Even when things looked bleakest, Dallas Green wouldn't give in and wouldn't let his players give in. No man did more to bring Philadelphia its first World Series victory in half a century.

Series Notebook: Dodgers nearing deal for Red Sox’ Fred Lynn

From Staff and Wire Reports

The first major deal generated at the World Series may be completed today. The Red Sox are on the verge of trading centerfielder Fred Lynn to the Dodgers in return for three players.

Two are pitchers Steve Howe and Joe Beckwith. The third player reportedly is the point of contention. The Red Sox are after infielder Mickey Hatcher. The Dodgers would prefer to give up outfielder Rudy Law. It appeared yesterday as though the Dodgers might relent and part with Hatcher.

•

Most Valuable Player of the Series Mike Schmidt said he'll donate the $5,000 scholarship that goes with the award to his alma mater, Ohio University.

Told that he also would be presented a $9,000 engraved gold watch, Schmidt joked: "You mean I don't get a car? I've already got a watch. Heck, I'll just trade it in for a car."

•

Phillies shortstop Larry Bowa has irritated a few members of the local press, but yesterday he almost got on the wrong side of a writer from Toronto.

"I've given them enough good years in Philadelphia that if I'm going to get traded, I think I've earned the right to tell them where I'm going to go. I'm not going to no Toronto," Bowa said in discussing the possibility of his being traded after this year.

At that point, a writer from the city in question laughed and said, "Thanks a lot, Larry."

Bowa realized immediately what he had said and grinned, trying to head off an international incident.

"You from Toronto?" he asked. "Well, uh, tell the fans that maybe in about five years I might want to go there."

•

Remember when pitchers used to be World Series MVPs? From 1955, which was the first year of the award, through 1968, the award was won by pitchers 12 times out of 14 years – just once by a reliever (Larry Sherry, 1959). From 1969 through 1979, the award has been won only once by a pitcher – reliever Rollie Fingers in 1974. What's happened since '69? The division playoffs. Before divisions, teams that clinched their pennants early could rest their best starters until the Series, giving one a shot at three Series starts.

•

Phils' reliever Tug McGraw has been a savior down the stretch and in both the playoffs and World Series, but, according to his wife, he almost wasn't a member of the team this year.

"If it wasn't for Dallas, I think Tug might have been out of baseball," said Phyllis McGraw.

"For three years here, they buried Tug. They didn't like Tug's up and positive attitude. Everything had to be cool. You know, like (Mike) Schmidt and (Garry) Maddox and (Greg) Luzinski."

•

The operator of the computerized scoreboard at Veterans Stadium apparently was not informed last night that the World Series was being played with the designated hitter. The scoreboard, at least through the early innings, listed the Phillies' Greg Luzinski and the Kansas City Royals' Hal McRae as pitchers in the lineups. Luzinski was listed with an 0-0 record.

Sweet Vindication

The win was delicious… the victory, more so

By Jayson Stark, Inquirer Staff Writer

It was a weird, eerie Phillies clubhouse, part asylum, part library.

There was chaos and the obligatory champagne shampoos. And there was also subdued quiet.

Steve Carlton, the winner of the game that made The Team That Wouldn't Die champions of baseball at last, retreated as always to the trainers room. It is strictly off-limits. No one tried to crash his private inner sanctum.

Through the glass in the doors, Carlton could be seen, in his private refuge, swigging from a magnum. The label could not be read, but it was not the Great Western brand that was being sprayed and hosed out in the clubhouse. Perhaps it was a selection from his own private stock, which is reputed to be impressive.

Once, Carlton came to the door, peered out to survey the madness outside, and then returned to a rub-down table to sit and sip.

Phillies filed in individually to join.him. Some stayed. Nino Espinosa. Ramon Aviles, who pressed an ice bag to his right eye. Larry Christensen, who reached out a plastic glass, which Carlton filled.

Dickie Noles barged in, embraced Carlton, and started to douse him with champagne, but Carlton backed off, smiled firmly but gently, and shook his head no. Noles grinned, shrugged, settled for another hug, and came back out, looking for something a bit more raucous.

Watching Carlton was rather like watching an emperor of some banana republic hunkered down in comfort while the streets outside explode.

Tug McGraw, the emotional antithesis to Carlton, fire to his ice, broke through and entered the trainer's room. He stood there, like a high-strung thoroughbred waiting to be shod, while they strapped an immense ice bag to his left elbow, then trussed the whole wing up in a sling.

"It's gonna stay right there the whole winter," McGraw said, patting the bandaged, fatigued arm. And then he danced a quick Irish jig, blew his nose lustily, wiped away tears, and strode back out into the reeling clubhouse.

It was a stange contrast, the reading room solitude of the trainer's room, Carlton nipping from the magnum slowly, deliberately, Christensen straddling a stationary bicycle, Aviles hunched on a table, Espinosa walking in circles. It was like they were riding out a blitzkrieg in some upholstered bunker, insulated from the screeching celebration.

And outside, in the clubhouse, there was the usual lunacy and madness.

Up on the TV platform, Dallas Green and Paul Owens collapsed into each other's arms, the manager and the general manager each sobbing.

Keith Moreland, the rookie catcher not too long removed from college, said, helplessly: "All I can do is laugh... and cry."

Greg Luzinski prowled through the mob, went to his dressing cubicle to his son, Ryan, and offered him a bottle. The little boy drank from it once and looked up at his father, and his eyes were red from crying. Luzinski looked down at him, smiled a parental assurance, reached out a large paw and mussed his hair. There were no words. None were needed.

And then Luzinski walked into the quiet of the training room, too.

A few feet away from that isolation ward, Harry Kalas was working his way through a series of interviews for TV, professional as always, fighting back the personal emotions that were surging through him.

And Larry Bowa sidled up behind him and drenched. Kalas with the remains of a bottle. The first drop had not trickled from the top of Harry's head to his chin before, never missing a beat, he turned and said: "And here's Larry Bowa, and what's your reaction, Larry?"

Bowa's voice was already hoarse, but wild-eyed and screaming he let the pent-up lava gush.

"All the experts were wrong. D-E-A-D wrong! The experts picked Pittsburgh and St. Louis and Montreal. Well, adios to them.

"And then the experts picked Houston in the playoffs. Adios.